Ritual and recycling: black mass in manufacturing

• Black mass is a by-product of EV battery recycling.

• Recovering and processing the chemicals can be costly.

• Recycling though could help improve the eco-credentials of EVs.

A Google search for “black mass” results in a slew of information on Satanic groups. So you might be surprised that the term has become well-used among those in the electric vehicle industry.

Although some anti-EV evangelists might like to imagine that the companies manufacturing the eco-friendly vehicles are practicing dark magic, the reality is less dramatic. As far as we know…

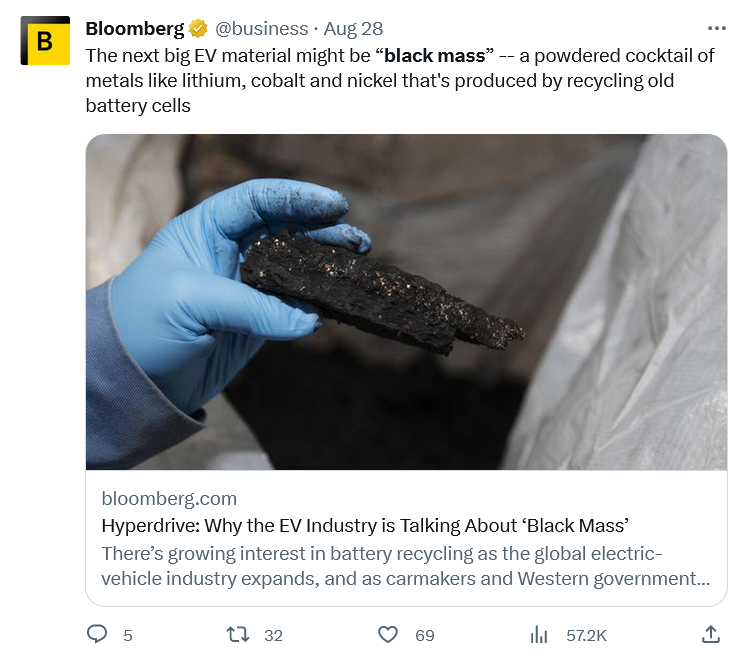

Actually, “black mass” is just a very literal description of the intermediate product that comes from recycling electric vehicle batteries, or scrap from battery plants. It’s a dark powdery mix of metals including lithium, cobalt and nickel that’s emerging as a commodity in and of itself.

With the expansion of the EV industry, interest in battery recycling has grown. In fact, black mass is even being mentioned in company earnings – including recent instances from Glencore, a commodities trader, and chemicals giant BASF.

The next big thing?

“There is definitely increasing interest from automakers in black mass now,” said Jesline Tang, analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights. Some have already announced partnerships or joint ventures to explore EV battery recycling opportunities, such as BMW, Ford and Mercedes-Benz.

The power of a black mass

The metallic powder is made by crushing and shredding batteries or battery cells, extracting unwanted elements, then refining the remainder. The majority of the input material, as things currently stand, is factory scrap from the production of batteries.

S&P Global Commodity Insights estimate that recycled materials will account for 15% of the global supply of lithium, 11% for nickel and 44% for cobalt by the end of the decade.

The adoption of EVs has been spurred by the improved performance and growing popularity of lithium-iron-phosphate cells (LFP), as well as reduced costs. However, it’s less profitable for recyclers.

At recent prices, nickel-cobalt-manganese batteries contain an average metal value of around $10,040 for every ton of cells, according to Fastmarkets.

EV batteries are comparitively eco-friendly – but can black mass recycling make it better?

Materials based on LFP chemistry have a much lower value of $3,935 per ton but can be more costly and technically challenging to process into black mass. That means less room for recyclers to make profit.

Hazardous cargo?

Further, some countries, including in Europe, classify open trading of black mass as hazardous. This is a key concern in terms of packaging, transporting and trading it.

“We’ve got lots of factories in Europe where we can shred batteries to make black mass but then it’s kind of stuck,” said Julia Harty, London-based analyst at Fastmarkets. “It’s a shame, as there’s so much attention on sustainability at the moment but yet the red tape makes lithium-ion battery recycling harder in Europe.”

Black mass becoming more mainstream might improve the environmental friendliness of EVs. Naysayers often point out that mining the battery metals is a huge sunk cost that would need tens of thousands of miles driven to offset.

If the elements are used and reused, with upwards of 99% of the battery materials useable in multiple generations of batteries, that might help address those sunk cost issues.

The nuance of black mass

“There is a nuance in battery recycling where companies that shred end-of-life batteries, and companies like RecycLiCo, that recover the valuable materials locked within the black mass – are both referred to as ‘recyclers,’” explains RecycLiCo Battery Materials CEO and Director, Zarko Meseldzija.

If battery materials can be recycled, then companies can “close the loop” on their lifecycle, reducing the carbon footprint of new mining activities. As demand for EV batteries grows, this could be critical in ensuring the sustainability of a new era of car manufacturing.