US-China relations – bluster, blunder, and strategy?

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

• Biden calls Xi a “dictator” – souring US-China relations.

• The rise of the Chinese tech sector is a thorn in every US president’s agenda.

• An increase in strategic anti-Chinese moves has characterized the Biden presidency.

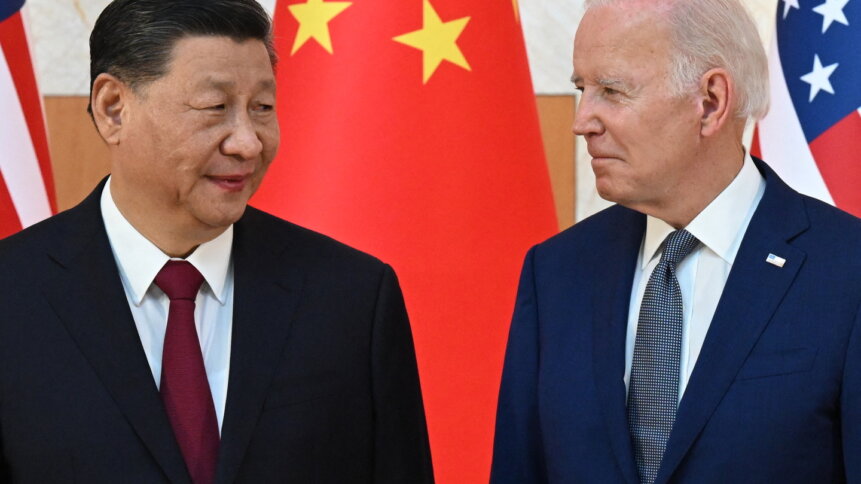

US-China relations have taken another spectacular nosedive, after US President Joe Biden was reported as telling a campaign event that President Xi Jinping was “a dictator.”

Leaving aside the question of whether his description is technically accurate or not – something that can be debated until the internet explodes – the timing of the comments could hardly be worse – at least from an outside perspective – and the response from Beijing has been predictable, not to say somewhat justified.

Just this week, US-China relations looked like they had turned the first positive corner of Biden’s presidency, when Secretary of State Anthony Blinken met with Xi Jinping and other high-profile Chinese ministers and business advocates in Beijing – the first time a US Secretary of State has made such a visit in five years.

Blinken, by no means an optimistic spreader of false hope, said the two countries remained far apart, but that, at the very least, they both held a desire to maintain a meaningful relationship. “The United States is committed to doing that,” he said.

US-China – the odd couple.

The very next day, the reports of Biden’s comment to a campaign event hit the media, and US-China relations went back to a frosty Square One.

Biden’s remarks “… seriously contradict basic facts, seriously violate diplomatic etiquette, and seriously infringe on China’s political dignity,” a spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry said. Seriously.

If the countries were the old married couple they sometimes resemble, it might well be time to at least talk to friends about who they used as their divorce lawyers.

In fairness to Biden, US-China relations have been complex for at least the whole of the 21st century so far.

From Bill Clinton’s signing of the US-China Relations Act of 2000, which normalized trade relations between the two economic behemoths, to China becoming the US’ largest foreign creditor in 2008, and the second largest economy in the world in 2010, things looked at least relatively stable – certainly, stable with hindsight – between the countries for the first decade of the century.

But the relationship between the leading exponent-nations of capitalism and communism in the world began to wobble again during the Obama administration.

A greater space for negotiation in US-China relations in the Obama era? Source: HO / ANDINA / AFP

There were a range of issues on which they differed – free speech, Hong Kong, the vexed question of Taiwan and its Schrodinger’s Cat existence as a free state and/or a part of “one China,” and China’s claimed ownership of the South China Sea – a vital trade route regarded by the rest of the world as international waters – as well as each country’s relentless and exhausting spying on one another.

The decline of the US-China relationship.

But as the Obama era ended and the (first) Trump era began, the usual tightrope walk by which the relationship between these economic powerhouses was maintained began to come undone.

Partly, that was down to a radical difference in the temperament of the incumbent in the White House.

When Obama lambasted China, it sounded as though he’d been studying all the secret documents in the world for a week before standing up to make considered points of political philosophy that underlined the nature of the United States and its international relationships.

US-China tensions grew during the Trump era. Source: Nicholas Kamm / AFP

When Trump lambasted China, it sounded like the bluster of a rage-tweet that had escaped into the real world.

In fairness to Trump though, the “Madman theory” of international diplomacy had the fingerprints of another former president – Richard Nixon – all over it, and it could be said that as president, Trump was an exceptional exponent of that art.

On more than one occasion, he scared the living daylights out of the world, with the result that previously cantankerous nation states sought other, less dramatic options.

The economic reality behind recent US-China relations.

But both Obama and Trump had to face one big issue, besides Hong Kong, Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the fundamental differences of approach to the notion of “freedom” in the different countries: China’s surging mastery of the key economic market of the early 21st century – semiconductors.

While initially trying to implement “the art of the deal” with China, in 2018, President Trump began the construction of a new age of US protectionism aimed specifically at China, and even more directly at its technological sectors, including chips, high-grade electronics, and the kind of computers that would be critical to the development of new and emerging technological realities.

After an initial round of tariffs on Chinese imports amounting to $50 billion, a second wave in the same year added another $34 billion of tariffs. China retaliated, with a pitch-perfect tit-for-tat round of its own tariffs.

Never let it be said that China doesn’t know how to play the game, particularly under the leadership of Xi Jinping – who had come into power during the Obama administration, and who remains in power to this day, having seen three US presidents come, and two of them go.

US-China: bluster and blunder.

The Trump era though was an age of bluster and overtly Sinophobic commentary. It was the era in which Huawei became a target of sanctions more or less intended to drive it out of the US market entirely, tainted with unproven accusations of “security threat” just as it was about to become a world-leading player in the smartphone market.

When Democrat Joe Biden won the White House (and once the ensuing insurrection of the criminally wrong had died down), many people expected US-China relations to significantly improve.

But that would be to mistake style for substance.

Biden has traditionally adopted the stance and the quietly uncompromising language of the Hollywood gunslinger towards China, rather than Trump’s loud and blustering technique.

But he has so far presided over one of the most protectionist presidencies in living memory, and has not been afraid to use similar socio-economic scare tactics to Trump’s government when it comes to painting everything Chinese with a brush of security suspicion.

The difference is that while under Trump such suspicion was often shrugged away as an outgrowth of the man’s Sinophobia, under Biden, it has clearly become a marker of political intent – and as such is taken and acted upon more seriously by others in Washington.

Biden – blunderer or strategist?

For Huawei, read TikTok – supposedly a security threat over the use that could be made of American users’ data, while Meta, Amazon, and Google continue to rack up multimillion (and now billion)-dollar fines for data misuse, both in the EU and in the US.

And Biden’s anti-China protectionist policies, like the tying of CHIPS Act funding to restrictions against selling high-tech chips to China or Russia (equating the two nations in the minds of Americans), and increasing attempts to shut down the Chinese technological supply chains, both by incentives for companies to “decouple” from their Chinese production bases and by the pressures of international diplomacy to shut down other avenues of chip supply, have put US-China relations on a colder basis than they have been at any previous point in the 21st century.

The response of China to the Biden line was described as “serious.”

That’s because Biden is facing up to a grim economic reality that has been clear to the three US presidents (so far) of the Xi Jinping era. Unless China is actively stopped somehow, it will significantly control what has been described as “the oil industry of the 21st century” – the creation, sale, and application of high-spec chips, on which depend the likes of generative AI, greener data centers, and even potentially quantum computing.

That would result in a greater American slump than any in recent memory – so there is a fundamental drive towards protectionism at the heart of US politics that will be the key economic concern of any president, Republican or Democrat.

Anyone trying brinksmanship with China needs to understand the country’s economic power.

The timing of the Biden “gaffe” – calling Xi a dictator – is of course likely to be seen as deeply unfortunate, coming just a day after Blinken’s meeting with the Chinese President.

Blinken described the meeting as “constructive,” without, as we’ve seen, sugar-coating the distance that remains between the two countries.

And what’s telling is that if it were genuinely considered a “gaffe” or an (increasingly typical) Biden misspeaking, White House officials would have been falling over themselves on all the news shows to “clarify” the President’s remarks – and to avoid the undoing of Blinken’s rightly praised work at taking the first steps towards a thaw in US-China relations.

The psychology of gamesmanship?

What you’re hearing is the sound of crickets. Official crickets with White House passes.

That suggests both deliberation, and an intention to make China swallow the “dictator” remark ahead of a rumored upcoming face-to-face meeting between Biden and Xi.

That in turn flies in lockstep with previous Biden administration protectionist actions, which have been delivered with a combination of specifically anti-Chinese impacts and a lack of any consolation given to Chinese feelings, either within the US or on the world stage.

The combination of Blinken’s first steps towards a thaw in US-China relations and Biden’s insult could well be an attempt to pull China into talks, while standing firmly by a negative, or at least actively anti-Chinese narrative.

What’s next for US-China relations?

Technically, it’s anyone’s guess. But it might make sense for another Biden administration economic thumbscrew to be deployed – after all, if China’s already angry about the “dictator” line, it’s probably a relatively safe time to “give it something to be really angry about.”

How much further China can be goaded in this high-stakes game of mahjong though remains to be seen.