The social media rulebook: content moderation

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Content moderation is an oft-ignored aspect of social media. The mechanisms that decide what’s hidden behind a disclaimer or removed from a site seem quite simple. It’s obvious what should and shouldn’t be accessible on social media… right?

The topic arose when Australian Communications Minister Michelle Rowland revealed that Twitter’s Aussie outpost had been ignoring correspondence. Months ago, Rowland enquired whether the social network would be able to meet the requirements of the Australian Online Safety Act. In response? Nothing.

the bird is freed

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) October 28, 2022

Layoffs at Twitter, which have been extensively covered in the media, included the company’s head of trust and safety and other members of that team. The Register reported that this was the result of Musk’s agenda of maximalist free speech on the platform,though this ethos has existed at Twitter since long before Musk’s acquisition. The company states that “as a policy, we do not mediate content or intervene in disputes between users.”

More likely, as with many of the changes, the layoffs were economically motivated.

YOU MIGHT LIKE

Is there a plan behind the Twitter journalists ban?

Musk has stated that a combination of artificial intelligence and human volunteers will take over from expensive employees. However, the Australian Online Safety Act requires Twitter to take proactive action to protect locals from abusive conduct and harmful content. So far, the employees haven’t been replaced yet. Analysts have noticed a spike in hate speech and disinformation on the platform since the layoffs.

According to Australia’s e-safety commissioner Julie Inman Grant, “anything goes these days on Twitter… They’re weaponizing. What do you expect? I’ve said this before, but you let sewer rats, and you let all these people who have been suspended back on the platform while you get rid of the trust and safety people and processes… and think you’re going to get a better, more engaging product that protects the brand, is pretty crazy.”

We began to wonder what Musk’s responsibility is when it comes to preventing certain content being posted on Twitter. In fact, what can any social media platform do to regulate its content?

Content moderation is a recent invention

Leaning heavily on a paper written by Kate Klonick for the Harvard Law Review, here’s a rundown of how online content moderation has evolved. Klonick’s paper is the first analysis of what platforms are doing to moderate online speech, starting with Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, established in America in 1996. Section 230 immunizes providers of “interactive computer services” against liability caused by user-generated content (UGC). In this sense, a website with a comment section would be classed as a distributor and thus couldn’t be held responsible for anything posted by commenters.

However, as soon as the site-owner exerts any influence over the comment section – by hiding or deleting a post – they are classed as a publisher, making a “conscious choice, to gain the benefits of editorial control.”

Using this framework, we could argue that there’s no benefit of editing UGC. However, (thinking pre-social media) what if in the comment section of a website selling umbrellas for $10, someone posted the name of a competitor selling umbrellas for only $7.50?

Alternatively, if an article has a comment section and the author vows not to interfere with UGC to ensure no liability, what will they do when someone posts obscenity and the advertisers that fund the website draw back?

Alongside that dilemma is the question of free speech. A website creator should be able to delete UGC that’s unpleasant, but where is the line drawn between genuine moderation and haphazard removal? Do we prioritize content moderation or users’ free speech? Here, a conflict arises: users’ First Amendment right versus intermediaries’ right to curate platforms.

At the dawn of social media, Twitter established a policy not to police user content except in certain circumstances, gaining the reputation among social media platforms as “the free speech wing of the free speech party.” Unlike Facebook and YouTube, it took on no internal content-moderation process for taking down and reviewing content.

In 2009, Alexander Macgillivray joined Twitter as General Counsel. In well-documented pushes against government requests related to user content, Macgillivray regularly resisted government requests for user information and user takedown. In January 2011, he successfully resisted a federal gag order over a subpoena in a grand jury investigation into Wikileaks.

Unfortunately, the parameters aren’t especially clear and, in some cases, they are flexible. For example, YouTube’s standards don’t allow gratuitous or explicit violence. When two videos of Saddam Hussein’s hanging surfaced on the platform in December 2006, both videos violated YouTube’s community guidelines at the time.

"Many big #tech companies rely on automated systems to flag and remove content that violates their rules, but… the findings from the Project’s report show that greater investments in #contentmoderation are needed" https://t.co/xqYzdYrYGR #ethics #internet #socialmedia #YouTube

— Internet Ethics (@IEthics) May 17, 2023

One video contained grainy footage of the hanging itself; the other contained video of Hussein’s corpse in the morgue. After some discussion, only the first video was allowed to remain on the site because “from a historical perspective it had real value.” The second was deemed gratuitous and removed.

At that stage in proceedings, the volume of content was manageable for human oversight, allowing for this kind of nuance to be established. One moderator at Facebook recalled that a “Feel bad? Take it down” rule was the bulk of her moderation training prior to the formation of [a team specialized in content moderation] in late 2008.

Then, three factors meant that YouTube and Facebook shifted from a system of standards to a system of rules:

- A rapid increase in users and volume of content

- The globalization and diversity of the online community

- The increased reliance on teams of human moderators with diverse backgrounds.

Crucially, and related to the Australian Twitter dispute, different countries have different definitions of obscenity. After some trial and error, it became clear that regional terms and geoblocking were less detrimental than having a whole platform blocked in certain areas.

Source: Stable Diffusion

According to Kate Klonick, “content moderators act in a capacity very similar to that of judges: (1) like judges, moderators are trained to exercise professional judgment concerning the application of a platform’s internal rules; and (2) in applying these rules, moderators are expected to use legal concepts like relevancy, reason through example and analogy, and apply multifactor tests.”

Who makes the call?

In the EU, the Digital Services Act, set to come into full effect in 2024, aims to:

- Better protect consumers and their fundamental rights online.

- Establish transparency and accountability framework for online platforms.

- Foster innovation, growth and competitiveness within the single market.

EU regulators have asked Musk to hire more people to fact-check and review illegal content and disinformation. However, across social media platforms, human moderators have become the second line of defence. Artificial intelligence is on the frontline.

Before delving into whether artificial intelligence is a worthy content moderator, it’s worth considering the implications of having people do it.

In 2020, Facebook agreed to pay $52 million to current and former content moderators in acknowledgement of the toll that the work takes on them. In September 2018, former Facebook moderator Selena Scola sued Facebook, alleging that she developed PTSD after being placed in a role that required her to regularly view photos and images of rape, murder, and suicide.

In 2022 Meta and its contractor Sama were sued again by a former content moderator, alleging human trafficking and poor mental health support. A case was brought brought in Nairobi by Daniel Motaung, who claims job adverts didn’t warn of the extremes that content moderators would see.

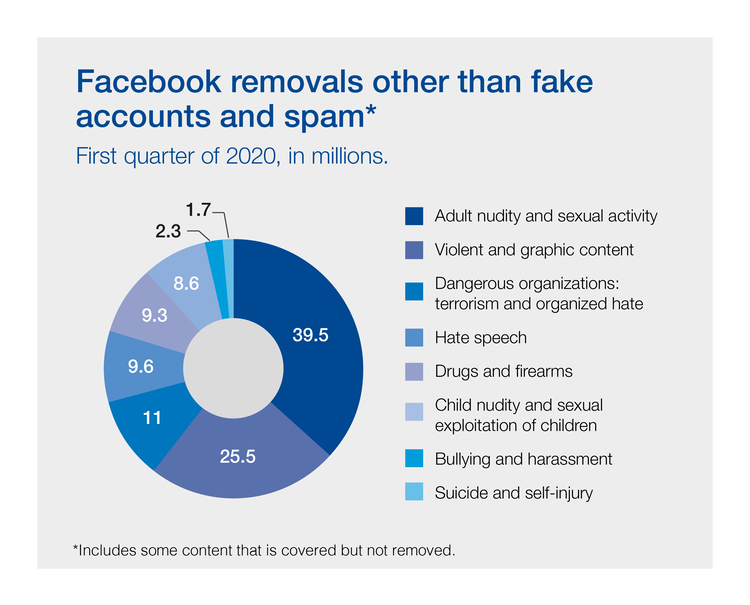

Facebook employs thousands of moderators to review content flagged by users or artificial intelligence systems to see if it violates the platform’s community standards, and to remove it if necessary.

A search for “content moderator” brings up 121 job posts on Indeed, the majority of which are advertised by TikTok. Its moderation policy states that “We moderate content in more than 70 languages, with specialized moderation teams for complex issues, such as misinformation.” Might this mean that the clear-cut violations of the sort that would cause distress are being dealt with by AI?

AI is being used to moderate content more and more, but in every use-case it requires some level of human oversight. Also, AI’s humanitarian track-record isn’t great: to make ChatGPT less toxic, OpenAI outsourced Kenyan laborers earning less than $2/hour. GPT-3 was a difficult sell, as the app was also prone to blurting out violent, sexist and racist remarks.

The outsourcing partner should be familiar for its involvement in Facebook’s scandals: Sama.

Sama markets itself as an “ethical AI” company and claims to have helped lift more than 50,000 people out of poverty. The traumatic nature of PG-ifying GPT-3 eventually led Sama to cancel all its work for OpenAI in February 2022, eight months earlier than planned. (or did past experience show that preventative measures would ultimately lose less money than paying off lawsuits?)

That being said, according to the World Economic Forum, by 2025 we’ll be creating over 400 billion gigabytes of data every day. At that scale, human-driven oversight will be impossible to maintain – ethically, at least – and automation is already well on its way to dominating content moderation.

If, as is widely predicted, AI is going to take on human jobs, this is an area in which it could productively do so – rather than, for instance, swamping the arts sector with AI content.

There are hazards even when a case seems clear-cut. Using PhotoDNA, it’s relatively easy for platforms to automatically identify and block child pornography. In 2021, during one of the COVID-19 lockdowns, a San Francisco father noticed that his son’s genitals looked swollen. He took photos on his Android phone to monitor the situation and made a remote doctor’s appointment.

Prompted by the nurse, he sent some of the images to his wife, to upload to the doctor’s office for review before the appointment. The photos were caught in an algorithmic net designed to snare people exchanging child sexual abuse material.

Obviously, the photos were entirely innocent, but they checked all the boxes for content that should be flagged. When something is flagged by Google’s filters, a user’s account is blocked and searched for other illegal content.

Yes, the photos in your Google Drive are only as private as you are law-abiding.

In this case, the data on the man’s Google account was handed over to police. Despite being found innocent, his access to the account has yet to be restored.

Social media sites need a new approach

Platforms create rules and systems to curate speech out of a sense of corporate social responsibility, but also, more importantly, because their economic viability depends on meeting users’ speech and community norms. Obscene and violent material threatens profits based in advertising revenue.

This shouldn’t be the ethos underpinning content moderation. Mozilla.social from Firefox is an entry for a more “healthy internet”: a powerful tool for promoting civil discourse and human dignity. According to Firefox, at the moment “our choice is limited, toxicity is rewarded, rage is called engagement, public trust is corroded, and basic human decency is often an afterthought.”

On May 4 2023, the social media platform released as a private beta. There, the content moderation approach is very different: “We’re not building another self-declared “neutral” platform. We believe that far too often, ‘neutrality’ is used as an excuse to allow behaviors and content that’s designed to harass and harm those from communities that have always faced harassment and violence.”

Like efforts to reduce carbon emissions, regulating social media content gets shouted down for being restrictive, infringing on American freedoms of speech and expression.

A new approach to content moderation is definitely needed; what that approach turns out to be, only time will tell.