• ispace – the Japanese company whose moon lander just failed to landon the moon, is preparing a second attempt.

• If it succeeds, it will be the world’s first commercial spacecraft to make a moon landing.

• The second attempt is carrying a tiny NASA lunar rover.

Japanese lunar technology company ispace is preparing to try again, two years after its first failed mission to put a lander on the moon. On Thursday, November 16th, executives announced that ispace will launch a new mission in the fourth quarter of 2024.

ispace – the final ifrontier? Via ispace.

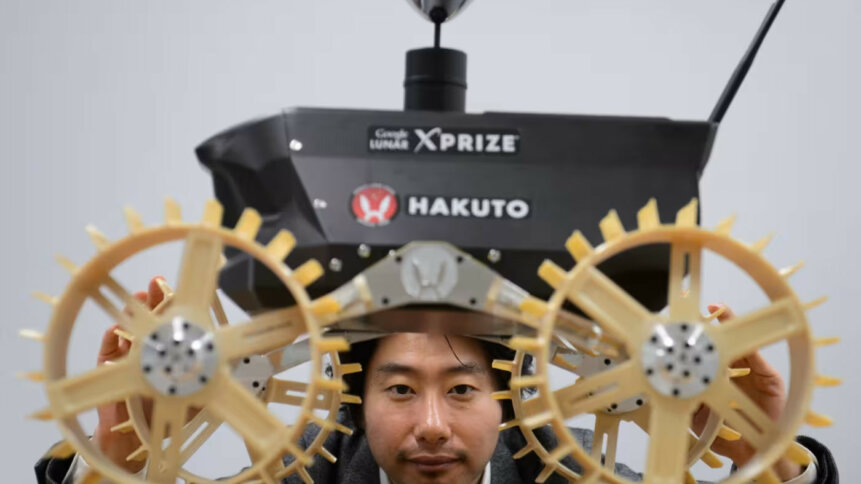

In December 2022, ispace launched its first lunar lander mission on a SpaceX Falcon 9. The lander, called Hakuto-R, spent over 100 days travelling to the moon. On April 26th, the world might have believed that the startup had made Japan only the fourth country to land a spacecraft on the moon.

Had it succeeded then, ispace would have been the first private sector enterprise to do so. Then, the livestream of the landing cut out as Hakuto-R made its final descent. 20 minutes later, the company’s chief executive and public face, Takeshi Hakamada, acknowledged that it was “unlikely” the craft had landed successfully.

It later transpired that the altimeter malfunctioned, causing the lander’s software to misjudge the distance to the moon’s surface. Ultimately, it ran out of fuel and crashed into the moon’s surface just moments before it had been meant to make contact.

Nevertheless, Hakamada declared the mission a “huge achievement.”

How ispace went wrong

An investigation by the Financial Times suggests the Hakuto-R failure was more than a mishap. Its demise followed months of financial, technological and corporate turmoil at one of the most ambitious projects ever entrusted to Japan’s private sector.

According to the investigation, the corporate environment within ispace didn’t allow failure and working conditions were “toxic.” Concerns were allegedly brushed off under pressure from shareholders, lenders and business partners to get the first mission off the ground.

A SpaceX rocket prepares to lift off with the Hakuto-R lunar lander in December on its journey to the Moon © Craig Bailey/USA Today Network/Reuters

There was such rapid engineer turnover at ispace that sometimes entire teams left at once. The company sold itself as a dynamic private sector operator in the mold of Elon Musk’s SpaceX or Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin by talking of business opportunities on the moon.

Perhaps back in 2022, Musk’s image was such that invoking it improved appearances. It is significantly more questionable whether the same is true as 2023 prepares to shuffle off into history.

Unlike Musk and Bezos, Hakamada felt that “the understanding of a greater number of people” was needed to build a new space industry. “Rather than raising private money, we wanted to become a company that can be assessed by capital markets.”

Shares took off (apologies – we were trying not to say “exploded”) and peaked at over ¥2,000 shortly before Hakuto-R was scheduled to touch down on the moon.

Internal analysis by ispace blamed a software glitch for the lander’s failure. It had a licensing deal to use software developed by Draper, the US company behind the guidance systems for the first manned moon landings in 1969.

The proposed landing site had been changed close to the mission launch, and Draper’s software was confused by the lander’s passage over the rim of a crater. It computed it was near the surface, when it was still 5km above it. Descending at a slow speed for gentle landing, the fuel ran out and the rest, as they say, is history.

And space garbage.

But mostly history.

Hakamada said the main issue was with Draper’s software but acknowledged the fault ultimately lay with ispace, since it had not adequately adjusted the software’s algorithms to reflect the changed landing site.

Doing it again – without the last-minute cataclysmic failure

Even though Hakuto-R’s debris is still scattered across the moon’s surface, ispace is back with a second lunar lander, this time called “Resilience.” Hakamada says the name represents “being strong and being able to bounce back, the quality of moving straight forward without defeat.”

Basically, it represents the definition of the word resilient, then. Although, given ispace’s first attempt, the phrase “bounce back” may seem to some to be a little ill-judged.

The catastrophe of the first mission enabled the company to glean plenty of information on subsystem performance, hardware, communications and orbital maneuvring. Going wrong just before landing is the best-case failure; everything up until that point was done right – which on current SpaceX form, is an achievement not to be sneered at.

Rovin’, rovin’, rovin’, moonside!

As such, the second lander will have much of the same hardware as the first did, said ispace’s deputy EVP of engineering, Yoshitsugu Hitachi. Travelling to the moon by the same route, via “low-energy transfer orbit,” Resilience will have the same dimensions and weight as Hakuto-R.

“The analysis of the Mission 1 landing failure clearly identified the causes and areas of improvement, so the main focus of Mission 2 will be on reviewing and improving the verification process that has already been implemented,” Hitachi said. “We are confident in the successful landing of the Resilience lander on Mission 2 and believe we can safely execute a soft landing and begin subsequent operations on the moon.”

The biggest difference between the missions will be payload. Perhaps fearing investor backlash after another failure, this time ispace has a contract with NASA, including a tiny lunar rover that will explore the landing site and collect samples of regolith.

The rover was designed to be “as small as possible, as light as possible,” ispace Europe’s managing director Julien Lamamy said. The rover, which weighs only five kilograms, has its own cameras, communications equipment and a 1-kilogram payload capacity. In addition to the rover, the Resilience lander will carry four commercial payloads.

The lander is expected to be assembled by spring 2024, before beginning environmental testing. From there, it’ll head to Florida for launch on a Falcon 9 rocket.

Tokyo-based ispace, which has offices in Luxembourg and Denver, is also working on a third mission that’s currently scheduled for 2026.