EU Digital Services Act: What is it and what has changed?

- The EU’s Digital Services Act now covers 19 major online platforms.

- Regulations cover transparency, removal of illegal content, and user control.

- Failure to comply will result in fines of up to 6 percent of their global revenue.

As of today, the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) applies to 19 ‘Very Large Online Platforms’ (VLOPs) and ‘Very Large Online Search Engines’ (VLOSEs). These are the apps and search engines visited by more than 45 million Europeans, or 10 percent of the continent’s population, every month, including Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), Snapchat, YouTube, and LinkedIn.

The legislation requires them to take more responsibility for the content hosted on their platforms, enhance transparency in their practices, and give users greater control over their digital experiences. It seeks to balance online innovation and free expression with the need to address issues like disinformation and harmful content.

European Commission executive vice-president Margrethe Vestager at a press conference to discuss the Digital Services Act in December 2020. Source: AFP

What is the EU Digital Services Act?

The first proposal of the DSA was brought forward on December 15, 2020 but didn’t become effective until November 16, 2022. This laid out the rules that all online platforms and search engines that operate in the EU will have to abide by, which include the following:

- Reporting and removing illegal content – Users should be easily able to report any misuse of the service, and specialized ‘trusted flaggers’ should be employed to seek out and remove illegal content. Platforms should act “expeditiously” to remove illegal content they host, including images of child sexual abuse, when flagged.

- Explaining moderation policies – Platforms should provide up-to-date terms and conditions that lay out their rights to restrict user access, which should be easy to understand. This includes the policies, procedures, measures, and tools for content moderation, highlighting whether they are human or algorithmic. They should inform users if their service has been limited and why.

- Ensuring seller legitimacy – If users can purchase products or services through the app, then it is the platform’s responsibility to ensure they are legitimate. They should also perform random checks for their legality.

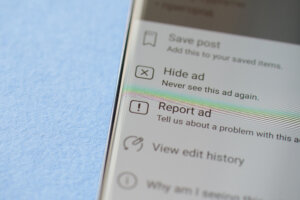

- Transparency over ads – Platforms should make it clear when they are displaying an advert rather than regular content.

- No ‘dark patterns’ – The interfaces used on platforms should not be designed to mislead users into, for example, buying products or giving away personal information.

- Transparency around recommendations – Platforms cannot use your data to make recommendations for search terms and other user choices and must disclose how they make recommendations.

- Crisis management – The activities of VLOPs and VLOSEs during crises will be able to be analyzed by regulators and they can place appropriate measures to protect fundamental rights.

- Child protection – Platforms must take measures to protect the privacy and security of children and cannot show them adverts based on their personal data.

- Annual risk assessments – Platforms must take part in annual risk assessments that check for potential problems with the spread of illegal content, misinformation, cyber-violence against women, harm to children, and adverse effects on fundamental rights. These will be balanced against restrictions on freedom of expression and be made publicly available. They will also have to take measures to reduce these risks, like implementing parental controls or age verification systems.

- User rights – Users should be able to make complaints to the platform and their national authority, as well as settle disputes outside of court.

Platforms must now take measures to protect the privacy and security of children and cannot show them adverts based on their personal data. Source: Shutterstock

Who has to comply?

While it isn’t due to be enforced in its entirety until February 7 2024, the European Commission has put forth numerous deadlines to encourage early adoption of the DSA by key players.

Online platforms were required to declare their number of active monthly users by February 17, so that it could decide the VLOPs and VLOSEs which should comply first and with the strictest requirements. These are:

- Alibaba AliExpress

- Amazon Store

- Apple AppStore

- Bing

- Booking.com

- Google Maps

- Google Play

- Google Search

- Google Shopping

- Snapchat

- TikTok

- Wikipedia

- X

- YouTube

- Zalando

However, when the February deadline comes around, all online platforms, regardless of user numbers, will have to comply with some of the regulations or face fines of up to 6 percent of their global revenue for a single infraction and 20 percent for repeated breaches.

What has changed?

Those 19 listed companies, whether they like it or not, now have to follow the extensive DSA regulations if they want to keep operating within the EU.

It should not come as too much of a surprise as, according to Reuters, the European Commission has offered to “stress test” the platforms to give them an indication of what they still need to do. According to a Commission spokesperson, this specifically assesses whether the platform can “detect, address and mitigate systemic risks, such as disinformation.”

Apparently, only five platforms agreed to this – Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and Snapchat – and all of them still needed to do more work to comply with the DSA. Indeed, when Ekō – a nonprofit that holds large corporations to account – submitted 13 hate speech and violent ads to Facebook, eight of them were approved within 24 hours. This research was only conducted at the start of this month.

When Ekō – a nonprofit that holds large corporations to account – submitted 13 hate speech and violent ads to Facebook, eight of them were approved within 24 hours. This research was only conducted at the start of this month. Source: Shutterstock

So far, none of the VLOPs and VLOSEs have publicly refused to comply with the DSA. However, retail platforms Amazon and Zalando have both disputed the fact that they have made the list.

Zalando said that “the European Commission did not take into account the majority retail nature of its business model and that it does not present a ‘systemic risk’ of disseminating harmful or illegal content from third parties.” An Amazon spokesperson told The Verge the company “doesn’t fit this description of a ‘Very Large Online Platform’ under the DSA” and is being “unfairly singled out.”

The latter, however, has begrudgingly added a feature that allows users to report illegal products being sold on its platform, despite claims that the “onerous administrative obligations” from the DSA don’t benefit its EU consumers.

Meta also now allows Instagram and Facebook users to challenge decisions to moderate their content, while TikTok users can opt out of personalized recommendations. Just this week, Google, Snap, and Meta proudly presented a list of steps they have made to meet the DSA’s requirements.

But will this be enough to appease the regulators? Time will tell, but regardless of this, it is unlikely that these VLOPs and VLOSEs will be able to rest on their haunches.

Will VLOPS play ball with the Digital Services Act – or abandon Europe altogether?

“The impact will be global,” Paul Meosky of the Electronic Privacy Information Center says in an analysis.

“It’s increasingly possible that these laws could prompt global innovation in how platforms interact with each other, their content, and their users. Providers will likely choose to update their algorithms and processes worldwide rather than operate substantially different platforms on different continents, benefitting all consumers globally.”