Worker shortages may see forced labor spike in tech supply chains

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

- Young workers in manufacturing hubs disenchanted with factory work.

- Labor shortage exacerbates issues of forced labor in tech supply chains.

- Companies not doing enough to eliminate exploitative labor practises.

If you are a business owner looking to cut costs at the expense of your lower-level workers, you might be fresh out of luck. Young workers in China and other Asian countries with significant manufacturing presence are, strangely, becoming disenchanted with the idea of relentless factory work.

The grueling hours, low wages, and intense physical demands have slowly contributed to what is now a significant labor shortage. A report from CIIC Consulting found that more than 80 percent of Chinese manufacturers faced staff shortages equivalent to 10 to 30 percent of their workforce in 2022.

Putting the specter of forced labor to bed

It has been 30 years since China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia first emerged as global manufacturing hubs, thanks to a combination of factors that propelled their rapid industrialization and economic growth. These include favorable geographic locations that provided access to key international markets, abundant labor forces capable of supporting various stages of production, and strategic government policies that encouraged foreign investment and technology transfer. ‘Made in China’ became synonymous with innovation, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. I

n recent years, discovers of forced-labor and child labor clouded the reputation of large technology companies, but there have been concerted efforts to clean up electronic manufacture’s supply chains.

These countries’ positions as manufacturing titans have remained that way for many years, but something has shifted. The young people that bosses relied upon to handle the strenuous manual tasks now have smartphones, connecting them with the wider world and allowing them to see a better life for themselves.

Employees work in a factory that produces LED lights for export in Jiujiang, China. Research predicts that digital worker shortage will reach 5.5 million people in the country by 2025. Source: AFP

Social media apps like TikTok have given them greater exposure to alternative working lifestyles and, as a result, high aspirations for themselves. They are seeking out employment outside of factory walls which is less physically demanding, has better working conditions, offers higher salaries, and provides more opportunities for development.

They join the service sector, start their own businesses, learn new skills in areas they are passionate about, or pursuit higher education to increase their prospects. Even skilled engineers are turning to well-paying roles in IT rather than working on factory machines.

In China, these children of the one-child policy era are viewed as ‘spoiled’ for turning their backs on the blue-collar jobs their parents worked to turn the country into a manufacturing powerhouse. In fact, these smaller family units have resulted in the new generation having less economic pressure to compromise wages and working conditions for job security.

In India, workers are migrating from factories to farms to take advantage of the government welfare schemes, with agriculture seeing an estimated 4.5 million increase in employment between 2021 and 2022.

YOU MIGHT LIKE

Global chain supply issues not going away in 2022

‘Google-ifying’ factories

To try and prevent their young workforce from slipping through their fingers, factory bosses have had to dig deeper into their pockets.

Wages in the sector have more than doubled over the last decade in both China and Vietnam. They are also providing more benefits like childcare, subsidized food, free yoga classes, and go-karting team-building events, as well as modernizing their factories with larger windows and open partitions, according to the WSJ. Many large corporations, like Nike, Hasbro, and Mattel, have reported rising costs due to the labor shortage.

But proper working conditions for these young people are not up for negotiation – if they can’t find something appropriate, they would rather do nothing at all. China’s youth unemployment rate hit a record high of 21.3 percent in June, according to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics, as, excluding the manufacturing sector, the job market is scarce.

Factories for garment manufacturers, like UnAvailable in Vietnam (pictured), are modernizing by introducing open partitions, cafes, and free yoga classes to attract younger workers. Source: UnAvailable

Forced labor, child workers and poor practise

Thanks to the defiance of the youth, China will face a shortage of 30 million manufacturing workers by 2025, according to its Ministry of Education. A large chunk of this will affect the smart manufacturing sector, as a report from Deloitte China and Renrui Talents predicts that the digital worker shortage will reach 5.5 million by that same year.

But there is a dark underbelly to this industry. Instead of tempting new recruits with benefits, there have been reports of forced labor throughout the electronics supply chain, from the mining of raw materials to production. Individuals, including children, work for long hours and low pay in dangerous conditions, and find themselves unable to leave due to threats or violence from their superiors.

Countries that dominate in electronics manufacturing, like China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Taiwan, often have weaker labor laws and don’t enforce them strongly. In 2019, the Migrant Workers Rights Network and Electronics Watch exposed Cal-Comp Electronics – a supplier to HP based in Thailand – for charging Burmese migrant workers an average of $660 each in recruitment fees – six times the legal limit in Myanmar. Factories in China specifically are known to rely on Uyghur state-forced laborers.

An artisanal miner holds a cobalt stone at the Shabara artisanal mine near Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The metal is used in the rechargeable batteries that power mobile phones and electric cars. Artsinal mining in the country is associated with child labor, dangerous working conditions, and corruption. Source: AFP

Tightening the purse strings

The problem has only been exacerbated over the last year. Along with labor shortages, electronics manufacturers are struggling with supply chain issues, and inflated energy & raw materials prices associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

There are also rising geopolitical tensions between China – where the electronics industry was valued at $350 billion in 2020 – and the West, particularly the US. Furthermore, business has yet to fully recover from the dip in profits when the demand for gadgets dropped dramatically post-COVID.

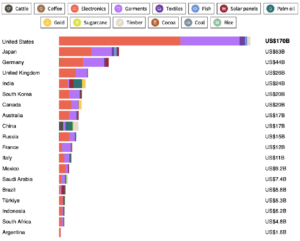

Tech giants like Google, Apple, and Sony are shifting production to other countries, including India, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Taiwan, and The Philippines, which have lower labor costs and a higher risk of forced labor. Leopards rarely change their spots, it seems. In May, the human rights group Walk Free released its annual Global Slavery Index which found that G20 countries spent the most on electronics out of all the imported products at risk of being produced with modern slavery, with a total of $243.6 billion.

The amount spent by G20 countries on products at risk of being produced with modern slavery. Source: Walk Free/Global Slavery Index

Ending forced labor

The key to tackling the issues of forced labor is supply chain transparency, but achieving this is not a simple endeavor for tech companies. This is because the elements that make up semiconductors and other intermediate components change hands up to hundreds of times before reaching the distributing company.

However, new legislation and import bans are making it harder to get away with this ignorance. For example, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act requires US companies importing goods from China’s Xinjiang Uyghur region to prove that forced labor was not involved in their production.

Some corporations take individual responsibility for their supply chains by conducting audits and inspections of suppliers, working with suppliers to improve working conditions, and investing in traceability technologies that enable them to track the journey of raw materials and components.

Hewlett Packard Enterprises came first in the Information and Communications Technology Benchmark of 2022 from KnowTheChain. It is consistently ranked highly in the annual lists, thanks to strong practises in responsible recruitment and human rights risk assessment. They are also leaders in robust policy implementation, prevention of abuse, and improved outcomes for workers who raise grievances.

Many leading tech giants, including Amazon, BT, Microsoft, and Salesforce, have joined the Tech Against Trafficking coalition. This group is working alongside experts to develop technological solutions that will help eradicate human trafficking and modern slavery. These include leveraging advanced data analytics to identify patterns of trafficking, developing AI-powered tools to detect online platforms used for illegal activities, and creating secure communication channels for survivors to seek help and support.

The median score of all the 60 companies analyzed for the KnowTheChain benchmarking report, which represents their efforts to address supply chain forced labor, was just 14 out of 100. Source: Shutterstock

However, the median score of all the 60 companies analyzed for the KnowTheChain benchmarking report, which represents their efforts to address supply chain forced labor, was just 14 out of 100.

According to the authors, this reveals “abject failure by most to demonstrate sufficient due diligence to identify forced labor risks and impacts in their supply chains, or take adequate steps to address them”. At the same time, the efforts of Hewlett-Packard and other front-runners prove it is possible to do so while remaining profitable.

Indeed, the rise of automation in all industries will likely make the need for such due diligence even more stark. The 2018 Human Rights Outlook highlighted how machines conducting routine tasks will only work to drive down labor costs, resulting in workers in developing countries competing for fewer jobs at lower wages.

The UN’s International Labor Organization estimates that 56 percent of manufacturing workers in Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, The Philippines, and Vietnam will have lost their jobs to automation by 2040.

Áine Clarke, Head of KnowTheChain and Investor Strategy, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, told TechHQ: “Rising geopolitical tensions and global events, such as the cost-of-living crisis, climate change and growing inequality, are causing supply chain vulnerability, leading some companies to shift sourcing to contexts in which they have less visibility.

“China’s ‘zero-Covid’ strategy – which created labor shortages and unreliable production outputs – and its trade war with the US saw some tech companies, such as Apple and Nintendo, shifting production away from China to countries such as India, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

“Decisions to re-shore are often commercially-driven with a lack of due diligence on the labor rights risks in new jurisdictions.

“The resulting lack of understanding of, and visibility over, working conditions, labor laws or civic freedoms afforded to citizens in the chosen countries can put workers at an increased risk of labor exploitation and forced labor.

“In India, labor laws were weakened to reboot the economy in the wake of the pandemic, while freedom of association and collective bargaining rights continue to be eroded globally.

“The impact on workers has been significant, ranging from health and safety issues, restricted hours and income, dismissal, non-payment of wages and restriction of movement.

“There is a significant gap between policy and practice when it comes to addressing forced labor risks in the ICT sector.

“Although a number of companies have human rights commitments, most have failed to consider how their purchasing practices are exacerbating forced labor risks within their supply chains, raising serious concerns about due diligence approaches across the sector.”