US action “violates international economic and trade rules” says China

The US government has been pursuing a more and more intensely Sinophobic (anti-Chinese) economic policy, particularly in regards to high tech developments and semiconductor supplies, for almost five years now. While under former President Trump, the US action went beyond standard economic protectionism and, like everything in that administration, was fueled by explosive rhetoric, the Biden-Harris administration has been turning the screws on China’s tech dominance almost since the moment it assumed office.

To ban, or not to ban…

That’s been intensified again this week, as senior advisers to the President have reportedly been seeking to ban Huawei (a leading Chinese phone and computer manufacturer) from dealing with any US component suppliers. The move is being treated as a potential response to Huawei’s return to some level of strength after it was put on a partial ban in 2019, and is thought to be seeking justification on the grounds of “national security.”

Beijing’s response came today from Mao Ning, a foreign office spokesperson. It was, perhaps unsurprisingly, uncompromising. “China firmly opposes the United States’ generalization of the concept of national security, abuse of state power, and unreasonable suppression of Chinese companies,” Mao said, adding that the US action, if carried through, would “violate international economic and trade rules.”

China, said Mao, would “firmly safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese companies.”

The importance of “firmly.”

“Firmly” is, or should be, a chilling word in that rebuttal. It’s the geopolitical equivalent of the schoolyard “Oh yeah? You and whose army?”

The two superpowers have been posturing this way for years, but since the advent of the Biden administration, the quiet economic war over technological dominance of the market has been turning up the heat at semi-regular intervals. The point being that the intervals are distinctly noticeable.

If you’re going to boil a frog, the legend has it, you start with a frog in a pan of cold water, and gradually turn up the temperature, so the frog doesn’t notice the increase – and then it dies. The US action under the Biden administration has involved intervals of heat intensification that have been relatively short, usually significant, and above all, noticeable.

Which is fine unless your frog has the world’s largest army, as well as technological dominance, and a good chunk of economic dominance, too. That’s a frog you really want to think twice before boiling.

The Sinophobic drift.

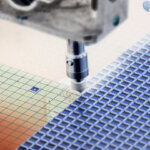

The US government has been working to re-establish a semiconductor manufacturing supremacy at home under the Biden administration, with moves like The CHIPS Act having at least the ostensible purpose of incentivising US companies to build world-leading semiconductor plants at home. But the further into the administration we advance, the more a Sinophobic tone has been noted in the US action.

First, companies were told that if they wanted to secure CHIPS funding, they would have to commit to not sending high-tech chips to China if there was even the possibility of them being used in a military context.

That should tell us something – not just that the US wants to hobble China’s runaway development of high-tech processors and products, but that there’s a military element involved in the US action. It would be possible to make the case that the US government is hedging its bets on supplying US chips to China’s military machine just in case its own armed forces end up fighting that machine at some future point.

The exploration of alternatives.

Reading both the room and their balance sheets, there then came a rash of US tech companies looking to pull their business – or at least their dependence – out of China, which has long been a favored country for mass production of high-tech products. Apple is a leading example of the breed, looking to increasingly disassociate itself with China and find alternative options for its technology supply chain.

Then there’s the intensification of geopolitical posturing between the two nations over the fate of Taiwan. Taiwan believes itself to be an independent nation. China believes that it belongs firmly to China. President Biden is on record as saying he will send troops to aid Taiwan in the event that China actively invades the country.

In as far as it goes, that’s just another day in the west wing. But Taiwan is one of the world’s largest producers of semiconductors. If China is barred from getting the high-tech chips on which its technological dominance depends through what have previously been legitimate supply chains, it necessarily heightens the attractiveness of taking at least a larger and more active interest in what is either its neighbor or its technological larder, depending on your point of view.

The importance of Taiwan.

And the growing reality of the world, recognised recently by Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger at the World Economic Forum in Davos, is that semiconductors are going to be the driving force in international geopolitics across the next fifty years, just as oil has been for the previous fifty.

The fact that the idea of banning Huawei completely from US technology suppliers is being floated, rather than simply announced, looks like either a foreshadowing, an attempt by the White House to prepare China for what’s coming, and warn it not to do anything precipitate in response, or potentially a negotiating position – a “We can do this, unless…” left hanging in the air in the expectation that China gives some further concession to the enforced re-balancing of the technological supply chain in America’s favor.

That “firmly safeguard” in response is on one level no less than Beijing has to say – it will be facing citizens who want a firm response to what will be seen as American economic aggression. But the next steps in the ongoing US action to rebalance the semiconductor supply chains will need to be taken very, very carefully if a sustained economic antipathy is not to erupt into the kind of war that gets people killed.

Is it just us, or is it getting hot in this pot?