Repairing your iPhone habit saves carbon (and cash)

Many believe that products should last longer — which means if it’s broken, it should be repairable, or if the user wants to prolong the item’s life, it should be upgradeable. That is only possible if a product is designed for repair and support is in place for repairers of all kinds. That is exactly why a movement known as “right to repair” is starting to gain ground — especially to push for laws that prohibit restrictions on those abilities.

For context, data by Statista shows that In 2019 alone, the electronic waste (e-waste) output of the world weighed the equivalent of 350 cruise ships. Three years later, it’s estimated to be 25 more – 375 cruise ships. – The US alone produced 6.92 million tons of e-waste in 2019, roughly 46lbs per person. Even in the European Union, it’s a severe issue simply because electronics are the fastest-growing source of waste in the bloc.

In the States, on March 14, this year, a bipartisan trio of US Senators introduced a bill that would require manufacturers to provide the tools and documentation necessary for consumers and third parties to repair electronic equipment. Dubbed the Fair Repair Act of 2022, the bill came about after an executive order was signed last July called on the FTC to hold smartphone manufacturers accountable for “making repairs more costly and time-consuming, such as by restricting the distribution of parts, diagnostics, and repair tools.”

The EU has outlined plans to establish a furtherance of its stipulations on manufacturers to ensure ‘right to repair’ for consumers. A consultation was launched on January 11 2022 on whether it should establish a consumer right to repair for situations that are not covered by the current legal warranty period. Currently, EU consumers have a right to have faulty products repaired, but only when a defect is present at the time of delivery and becomes apparent within the legal warranty or guarantee period, which in most EU member states is two years.

Why legislate for the “right to repair”?

Manufacturing new devices still largely rely on polluting sources of energy. To grab an example, let’s look into Apple’s manufacturing data. Mining and manufacturing materials for the newest iPhone, for example, represents roughly 83% of its contribution to the heat-trapping emissions in the atmosphere throughout its life cycle. That’s an up-front carbon cost, which (if things went Apple’s way) would be a repeating cycle every year as every user invests in a shiny new model.

For context, electricity generated from burning fossil fuels constitutes the largest environmental impact for most products as they use power throughout their lives. Comparatively, for a washing machine, about 57% of the total environmental damage happens before sale. Therefore, the ecological and economic arguments for a ‘right to repair’ rule is, as advocates say, one and the same, but are both contingent on companies making parts, tools and information available to consumers and repair shops to keep devices from ending up in the scrap heap. When repairs are made too difficult, it encourages a throwaway culture. Manufacturers’ profits are good, but ecological impact is maximized.

YOU MIGHT LIKE

Sustainability is now a focal point for businesses

Some manufacturers encourage a culture of planned obsolescence — the idea that products are designed to be short-lived in order to encourage people to buy more stuff. That would inevitably contribute to more wasted natural resources and energy use, especially when climate change requires movement in the opposite direction.

Repairs, not replacements of electronic devices would certainly be much better for the environment, leading to a reduction in resource use, fewer greenhouse gas emissions and less energy consumption.

Do tech giants share the sentiment?

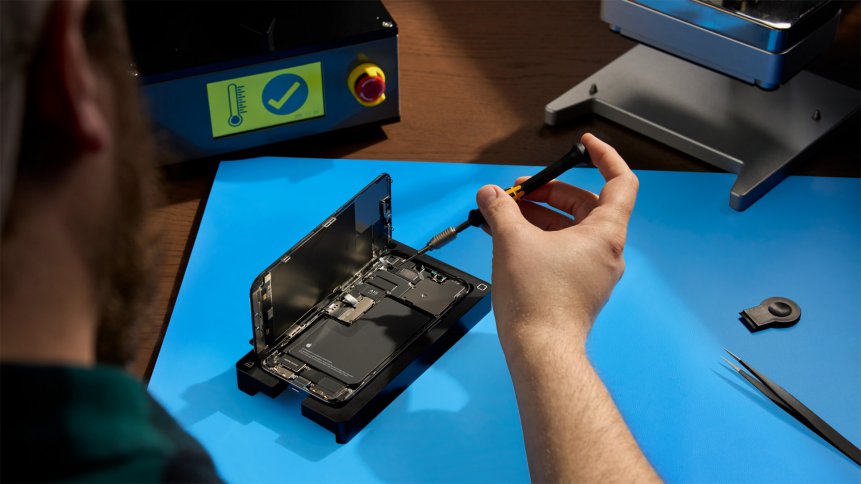

Within the last few months, tech giants including Samsung, Google, and Apple have been announcing programs that would allow regular consumers and independent repair shops to buy official parts, so they can more easily repair devices. In fact, Samsung and Google have partnered with repair specialists iFixit, while Apple’s Self Service Repair program was just recently launched, giving just US customers for now, tools, parts, and instructions to fix common iPhone issues.

Even Microsoft has been integrating repair and serviceability into a number of their Surface products, like the Surface Laptop, and just last year announced a partnership with iFixit to sell tools and distribute guides to repair several Surface products. Dell also announced the Luna concept, which is an ethos of promotion of a significantly more modular device style, thus allowing for more ease of repairability and recyclability.

Finally, it remains to be seen how many consumers will actually fall in with the self-repair culture. After all, fixing an iPhone, digital watch or even a laptop is no simple matter, even when parts are available. But it would be good to have the option to re-use, repair and upgrade rather than buy new — and a third-party repair industry would be good news for the state financial authorities of many countries. Small businesses tend to pay tax, after all.