Hydrogen fuel cells – the future of clean data centers?

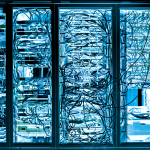

As our reliance on cloud services and increasingly advanced technology like AI continues to amass more data than ever, the question of how to make power-thirsty data centers cleaner is becoming a serious consideration for the world’s tech leaders.

Data center operators have turned to wind and wave energy in the past, while efforts to cool them to make consumption more efficient have led internet companies to construct them in countries with colder climates, like Iceland.

In fact, this quest has given rise to a data center cooling equipment market predicted to be worth US$24 billion by 2024.

This week, however, Microsoft announced a milestone in green data center energy, successfully using hydrogen fuel cells to power a row of data center servers for 48 consecutive hours.

The test was part of the technology firm’s goal to eliminate dependency on diesel fuel by 2030, when it’s also aiming to become carbon-negative. In a blog post, Microsoft said the feat could “jumpstart a long-forecast clean energy economy built around the most abundant element in the universe.”

At present, Microsoft says that diesel accounts for less than 1% of Microsoft’s overall emissions. Its use is confined to Azure data centers where, like other cloud providers, diesel-powered generators support continuous ‘five-nines’ availability even in the event of power outages and other service disruptions.

Mark Monroe, principle in infrastructure engineer on Microsoft’s team for datacenter advanced development said these generators were both expensive, and “don’t do anything for more than 99% of their life.”

With costs plummeting, hydrogen fuel cells are becoming a viable alternative, if only (at present) for the limited role in supplying emergency backup power.

An Azure datacenter outfitted with fuel cells, a hydrogen storage tank, and an electrolyzer that converts water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen could be integrated with the electric power grid to provide load balancing services, Monroe said.

Microsoft could start up the hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity for the grid, with an electrolyzer able to be turned on during periods of excess wind or solar energy production, to store the energy as hydrogen. This infrastructure, said the firm, represents an opportunity for Microsoft to play a role in what will be a “dynamic kind of overall energy optimization framework that the world will be deploying over the coming years.”

“Hydrogen-powered long-haul vehicles could even pull up at data centers to fill their tanks.”

The seed for using hydrogen fuel cells for backup power was planted in spring 2018, when researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colorado, powered a rack of computers with a proton exchange membrane, or PEM, hydrogen fuel cell.

But even before that, the firm has been exploring ways to use fuel cells, beginning to explore the technology in 2013 with the National Fuel Cell Research Center at the University of California, Irvine, where they tested the idea of powering racks of servers with solid oxide fuel cells, or SOFCs, which are fueled by natural gas.

“They have the ability to make their own hydrogen out of the natural gas feed that they get,” Monroe explained. “They take natural gas, a little bit of water, they heat it up to 600 degrees C, which is the temperature of a hot charcoal fire.”

That’s hot enough for a process called steam methane reformation that generates a stream of hydrogen atoms for electricity generation.

Microsoft has continued to explore the potential of SOFC fuel cell technology to provide baseload power, which could free data centers from the electric power grid while making them 8 to 10 times more energy efficient.

For now, though, the technology remains too expensive for widespread deployment.