Does AI deserve a producer’s credit?

In the Marvel film franchise, the superhero Iron Man is assisted by J.A.R.V.I.S., an AI system that delivers strategic guidance and damage reports. Iron Man’s armor is occupied by Tony Stark, a brash industrialist.

The Marvel Comic Universe has grossed over US$22.5 billion in global box office.

Now, some technologists, investors, and executives hope that the type of artificial intelligence systems featured in the movies will become industry realities that increase the profitability of entertainment products.

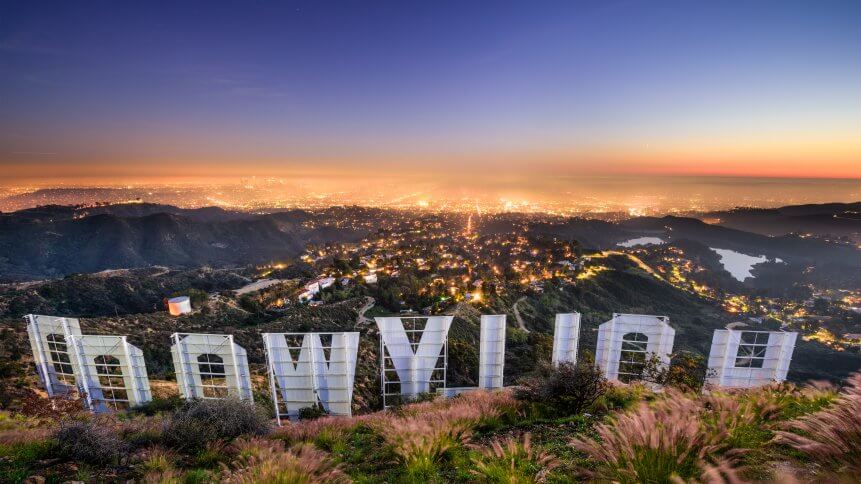

Beneath the creativity and glamor of Hollywood, there are high investment stakes. Tech vendors are trying to guide the development of entertainment IP through predictive audience analytics, more efficient planning tools, data-driven decision making and risk avoidance strategies, and machine learning techniques that illuminate previously overlooked patterns in historical data.

But even though many of these tools are being promoted as methods of risk management, they could inspire mindsets that are actually more blind to particular forms of risk.

Data-driven decision making you can trust?

It’s a counterintuitive phenomenon that is happening across industries. Chief Technology Officers are bombarded with an array of third-party vendor products that purportedly contain AI and purportedly will make their jobs easier. But the AI-powered analyses can be misleading.

Executives need to ask tough questions. What if the AI was trained on incomplete or biased datasets? What if it isn’t really AI? And is AI supporting the business’s core product, or fundamentally changing it?

Hollywood is being sold on the technological concept of AI-powered “decision support.” For example, a producer can swap out different actors within an analytics platform to see the implications across global territories and different methods of media distribution. The predicted impact upon revenue is sometimes further qualified with a “confidence level.”

While I’m not suggesting that these technologies are necessarily faulty, the deployment of these technologies is sometimes premised upon the false assumption that talent is creatively interchangeable. A particular actor or director may not be creatively right for the project at hand.

Yes, maybe one actor is well-regarded by a valued demographic and has the quantified social media followers to prove it. But if pairing that person with the material causes the overall project to suffer creatively, you might not inspire a substantial percentage of those followers to actually go out and buy tickets.

Films are always risky bets. Established intellectual property improves the odds but still does not guarantee success, as many high-profile flops have demonstrated. Film producer and financier Ryan Kavanaugh tried to gain a competitive advantage by utilizing a Monte Carlo model. His company later filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy (due to a variety of reasons).

YOU MIGHT LIKE

IBM Watson’s Lexus ad shows how AI can augment creative

When AI can miss the point

Nevertheless, risk analysis and predictive analytics have yielded benefits for many industries. Within the context of marketing, a multi-pronged approach to analytics can improve the ROI on targeting, lead nurturing, product recommendations, and retention tactics.

But the entertainment industry is particularly tricky. The important variables are creative, subjective, and cultural. The production process doesn’t accommodate many pause periods for reflection. In other industries, companies can test out their strategic business hypotheses with a lesser degree of investment and robust analytics quickly show them the response.

The hypothesis is either validated or rejected by the market over fast, cost-effective cycles.

However, entertainment product represents more of a creative hypothesis and it requires a determined long-term investment in a particular creative direction. Data-driven talent adjustments do not happen in isolation. Rather, they could fundamentally disfigure the creative hypothesis itself.

Many media companies are still throwing darts into the darkness. It would be unwise to forgo the technological equivalent of a flashlight. But it’s also unwise to operate under the delusion that you can see and foresee everything when you really can’t.

When human interaction should come first

In March, The Walt Disney Company acquired 21st Century Fox for US$71.3 billion, but most of the Fox movies released this year were considered to be flops. During an August quarterly earnings call, Disney chief executive Bob Iger admitted that the studio’s performance had failed to meet Disney’s expectations at the time of the acquisition.

Last year, Disney pulled in an impressive US$59.43 in global revenue. But in this particular instance, and at this particular time, it seems that the flashlight was too dim.

Recently, protestors called for the boycotting of the live-action “Mulan” film after the lead, Chinese-American actress Liu Yifei, expressed a controversial opinion about the political situation in Hong Kong. The actual impact on box office is not yet determined. When actor Kevin Spacey was accused of sexual misconduct, the producers of “All the Money in the World” recast the role and reshot all of his scenes, costing them at least US$10 million.

#BoycottMulan is trending after Liu Yifei, the star of Disney’s live-action remake, showed support for Hong Kong police in the city’s chaotic protests. pic.twitter.com/eOV5SWcQVx

— Pop Crave (@PopCrave) August 16, 2019

Could an algorithm have predicted these developments? Perhaps AI could have ran proposed cast members’ old tweets and interview statements through affective analysis and produced a psychographic profile of them.

But there’s a simpler way of figuring these things out. It’s called human interaction. It’s the true foundation of any collaborative effort. An algorithm might tell you to cast someone because it sees how well they historically sold tickets in a particular territory. But it doesn’t see the person.

Is AI supporting your product?

It’s possible that some of these AI tools provide a level of value other than the type that is being directly marketed. An AI-influenced approach to the green-lighting of films may not consistently deliver better ROI. But the perceived advantages of analytics may provide a higher degree of confidence to institutional investors who would otherwise be wary of the entertainment industry’s high-risk product.

There are lessons here that transcend industries. AI can improve the odds of success in certain circumstances, but those probabilities may also depend on the ways that corporations integrate new technological inputs.

If you’re a CTO, ask yourself: Is AI supporting your product, or fundamentally changing it? Is it redirecting your focus in ways that are valuable, or causing you to overlook something that is critical?